Authored by: Shambhavi Tiwari, Batch of 2028

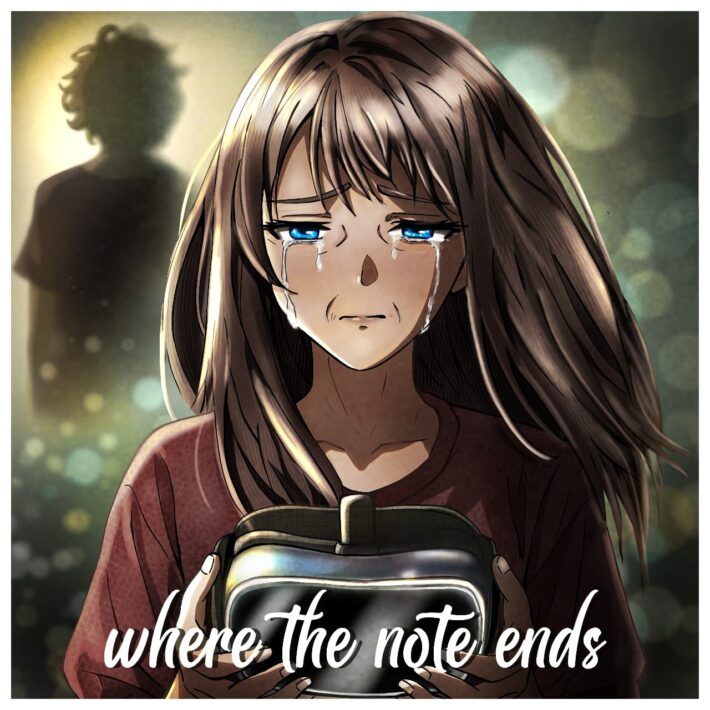

Caricature by: Shriyans Mohanty, Batch of 2028

Trigger Warning: This blog contains sensitive discussions of suicide, depression, and grief. It is not intended to offer medical advice, provide solutions, or romanticize self-harm. If you need someone to talk to, here are some trusted helplines you can contact for immediate support:

– 1life: 7893078930 (24/7 availability)

– Tele Manas: 14416 (24/7 availability)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

When someone is deeply depressed, their thinking narrows – not into delusion, but into a tunnel vision of pessimism. Choices become binary. It’s not life vs. death. It’s this pain forever vs. an end to the pain.

When someone is suicidal, they rarely make choices based on what’s truly right or meaningful, but on a desperate urge to stop the pain. The core belief in this article is that the perspective of the deceased matters. Too often, conversations around suicide focus only on those left behind, the survivors reduced, while the person at the centre, in their last act.

This blog does not aim to excuse, glorify, or lecture on the painful subject of suicide. It’s not a solution either. It’s an attempt to open a door into the complexity of the autonomy of a suicidal person, and why listening to the voices we’ve lost, however imagined, fragmented, or posthumous, is sometimes the only way to shift how we talk about suicide at all.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Meera hadn’t moved since the incident. She sat on the edge of her bed, spine curved like a question mark, still clutching the letter she had received from the police, her son’s suicide note. The paper had softened at the creases, corners wilting under the weight of her hands, sweat, and grief.

The note was curt. No apologies. No explanations. Just a line or two, like a final breath, let out into the world.

It didn’t say why.

And that, somehow, hurt more than anything he could have said.

The house remained still, quiet in a way that didn’t feel peaceful. The kind of quiet that wrapped itself around you like a cold hand. Her husband moved like a ghost down the hallway, barely eating, barely sleeping. They had both become shadows of people who had once laughed, fought, worried over school reports, grades, and argued about dinner, thinking all those moments meant they knew their child.

People knocked on their door every day, called her every day, reaching out to help them in any way possible. But it didn’t matter; the only thing that mattered to her was that her son was back in their home, eating the food she had given him, playing his video games. No one could ever give her that.

Her husband hadn’t spoken in days; all he did was look at old albums, moving from their son’s desk to the main gate, perhaps hoping he would ever return. They were experiencing a piercing pain, the kind that made her want to give up, the kind her son might have felt before giving up.

Their son, Madhav, was gone forever.

They didn’t have to think when naming him. Sure, it carried a part of her faith- Madhav, beloved offspring of Meera. Fitting for a child such as hers.

He was sweet. From the moment he came into the world, blinking up at her with wide, owl-like eyes, he had felt like something whole. Something complete. He barely cried. He curled his fingers around her thumb like he was promising to stay.

Her little honeypot. The kind of baby who smiled in his sleep and reached out in his dreams.

Madhav, named not just after God, but after love itself. Maybe, just maybe, if she called him desperately enough, he would return.

But life was cruel.

And people are even worse. She had received some calls from his university to give them the “permission” to use one of her son’s inventions, a simulator. Vultures. All of them. Circling his body before it was even cold.

She hadn’t cared. Not about the calls, not about the emails, not about the painfully rehearsed condolences from professors or about the woman sitting in front of her, explaining the “situation” to her.

She hadn’t even really listened until the woman mentioned, almost in passing, that this simulator, his invention, might hold something more than code. That it might hold his memories. That made her listen.

And for the first time in weeks, Meera had looked up from her bed, her fingers still curled around his note, her lips dried from silence. And she moved towards his room.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Grief Inertia.

In clinical terms, it’s a state where basic functions like movement, appetite, and speech slow dramatically. But it’s also cognitive: time distorts, and decision-making becomes impaired. In cases of suicide loss, meaninglessness compounded inertia. With no narrative closure, no clean cause-and-effect, the mind resists re-engagement. As a result, people don’t move on; they keep on questioning.

When a child dies by suicide, the grief experienced by a parent isn’t just loss; it is a state of collapse. The natural order is reversed. Parents aren’t supposed to outlive their children. And when the cause is suicide, it adds a layer of confusion, guilt, and shame that few other losses carry. The loss is especially brutal because parents often build their identity around care, protection, and presence. After a suicide, all of that feels like it failed.

How can we help someone going through such a loss?

Truthfully, we can only offer support. This kind of grief doesn’t ask for comfort. It asks for meaning, and we often find none.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Meera held a binocular-shaped device in her son’s room. He was messy. Always was. He hated it when anyone touched his things. She stood still, afraid even now to move something out of place. Afraid of rewriting him by accident.

The device was heavier than it looked. She didn’t know what it did. Some kind of VR headset, she thought. His last project. Or just a toy. She didn’t know; she just raised it to her eyes. She flinched as a voice spoke from it! It lingered in the air, synthetic yet disturbingly close to her son’s real voice.

My Beta, she wanted to weep.

“Welcome to the world of Maddy. From now onwards, you are not someone with freedom of thought; you are me. Enjoy the landscape of my mind.”

After that, Meera lost all her thoughts, not in the forgetful, distracted way people often describe, but in a far more unsettling sense, like her mind had been forcibly emptied. Her inner voice, once filled with questions and hesitation, had gone silent. In its place were flickering images, broken sounds, half-finished sentences that didn’t belong to her.

A hallway she’d never walked down. A notebook she’d never written in. A voice that wasn’t hers, whispering things she didn’t want to hear. They played across her vision like projection reels, too fast to fully grasp, too vivid to ignore.

She wasn’t just Meera anymore. She was also Madhav now.

Inside the VR

There was a woman in front of him, holding a tiny spoon like it was magic. “Here comes the rocket!” she whispered, her eyes twinkling, and Madhav, barely five, opened his mouth in awe. She fed him mashed banana and smiled so wide it made him giggle, like her joy had nowhere else to go but into him.

His father entered the room, towel over his shoulder, hair still damp. “Running late again?” he asked, but there was no urgency in his voice. Just affection. He crouched beside them and gently tugged a sock onto Madhav’s tiny foot.

“You’re the reason we’re always late, babu,” he teased, tapping his nose. Madhav laughed, sticky-mouthed and full of warmth.

He didn’t know what time meant, or responsibility, or pressure. All he knew was this moment, soft voices, warm hands, gentle eyes, and the certainty that he was loved, wholly and without question, even by himself.

The VR distorts

Madhav was feeling disturbingly hateful towards himself today. He wasn’t entirely sure where it came from, but he could feel it in his chest like something sour trying to claw its way out. He was twelve years old and already exhausted by the idea of being himself.

He hated how easily other kids floated through the day, how they laughed with no need to check if the timing was right, how they didn’t seem to shrink under their skin. It annoyed him, and sometimes he made himself feel better by imagining something bad happening to them.

Nothing serious. Just small things, like tripping in the hallway or getting called out in class. He’d pretend he didn’t care, but he always noticed when something finally humbled them, and it gave him a sense of control he rarely felt otherwise.

He knew that wasn’t a good thought to have. But it was there. He didn’t push it away. If anything, he kept it close, like a defence mechanism. If he couldn’t be happy, he didn’t want to be the only one who wasn’t.

Sometimes he’d test people, say things that were half true, half bait, to see how they’d respond. If they took him seriously, he’d roll his eyes and accuse them of being dramatic. If they didn’t, he’d take it as proof that they didn’t care. There was no way to win, but part of him liked it that way. At least he got to decide the rules.

Madhav could be cruel, even to the people who loved him. He hated how much he needed them, how much it hurt when they misunderstood his silence or missed his signals. Instead of telling them, he’d go quiet for days or say something sarcastic, just to push them away first. It felt safer to be alone on his terms than to risk being abandoned on someone else’s.

There was a part of him that didn’t want to get better. Not because he liked feeling this way, but because the pain had become familiar. Reliable, even. If he suddenly started feeling okay, what would that say about everything he’d been carrying? That it wasn’t real? That he’d wasted years being miserable for no reason?

He would rather be in this hatred forever.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Self-loathing often settles into the body like a cold that never fully goes away. Not severe enough to be an emergency, not visible enough to draw concern, but just persistent. Lingering. It colours everything without ever naming itself directly. It’s a form of internalised contempt, a self-directed anger that becomes easier to manage when projected outward. This is especially common in teens who feel chronically misunderstood or emotionally invisible. Anger, unlike sadness, feels active. It gives the illusion of control.

When emotional pain becomes familiar, it can feel safer than recovery. Healing, after all, demands you confront how long you’ve been hurting. That’s a terrifying task, especially for someone still learning who they are.

But over time, this cold can deepen. It spreads. Quiet resentment becomes isolation. Sadness becomes shame. And shame, if left unchecked, starts to rot your sense of self. What was once manageable now clogs your thoughts, your relationships, and your future.

When left untreated, this cold turns into pneumonia.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

At sixteen, Madhav no longer saw himself as someone in crisis. He saw himself as someone fundamentally flawed but functional. He woke up, went to school, answered questions in class, passed his exams, and held conversations well enough to be called “mature.”

Madhav had begun to fear emotional intimacy. He would ghost friends for no reason. Cancel plans at the last minute. He’d answer texts hours late with flat replies like “cool” or “yeah” just to end the conversation.

When someone called to check in, he ignored it. And then later, he’d lie in bed and convince himself he had no real friends. He saw abandonment everywhere – real or imagined. And he often did the abandoning first, just to be safe.

He thought that would change when he met Aanya.

Smart, patient, the kind of person who didn’t just listen but paid attention. She remembered small things he said in passing and brought them up later, not to quiz him, but to show she’d been holding onto them.

She looked him in the eye too long, like she could see something in him he didn’t want to be noticed. And that made him panic. He liked her. He didn’t like that he liked her.

Because she made him feel visible. And visibility to him was always a prelude to rejection.

He hadn’t felt seen in a long time, not since things got heavy in his head. The kind of heavy that made getting out of bed feel like a task, answering messages felt like a performance.

So he played it cool. Detached. He joked when things got real. Teased her brutally instead of thanking her. He let her care, but only from a distance. Just far enough that she’d always be a little unsure where she stood.

Still, she stayed longer than he expected. Gave him space when he pulled away. Showed up gently when he seemed off. And every time she reached for him emotionally, he offered her just enough: a vulnerable line late at night, a story he hadn’t told anyone, a quick, “I don’t usually say this, but…” Then followed it with a hard reset the next day. Cold texts. Dry replies. Deliberate silences.

It was a game, but not a conscious one. He wasn’t trying to hurt her. He just didn’t know how to accept love without waiting for the part where it left, and a deeper part of him wasn’t sure he deserved it, anyway.

Eventually, it ended.

She didn’t yell. She didn’t accuse him of anything. She just sat next to him after class one day and said, “I don’t think I can keep doing this.”

He shrugged. “Doing what?”

“Trying to matter to someone who’s already decided I don’t.”

He felt a whiplash at this.

He wanted her to stay, even if he made her feel small. He wanted her to push harder, prove she was different. He wanted her to fight for him so he didn’t have to fight for himself.

Later that night, he replayed the conversation and twisted it in his head until it sounded like betrayal.

He told himself she gave up too easily. That she never really got him. That she wanted someone “easier.” That she couldn’t handle depth, he built her into the villain, brick by brick, not because she was one, but because he needed a reason not to blame himself.

And still, some nights, he scrolled through old texts and found parts of her he missed, the way she said his name like it wasn’t something heavy, the way she never rushed to fix him, the way she waited.

He would never tell anyone, but a part of him wanted her to reach out again. Just once. Just enough to prove he hadn’t ruined everything completely.

But she never did.

“She’s the worst. She’s horrible. She’s just like everyone else.”

That’s what he told himself, again and again, like a mantra. Like if he said it enough times, he could turn his humiliation into anger. If he painted her as the villain, maybe he wouldn’t have to admit how much her leaving cracked something in him open. Because if she had screamed, if she’d said something cruel, maybe he could’ve hated her cleanly.

He said it to his friends too, once or twice, casually, dismissively, in the way people talk about someone they’re trying to erase.

“She’s so dramatic. Thinks she’s better than everyone. Whatever. I’m over it.”

But he wasn’t.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Is it fair to hate someone for choosing themselves? For walking away from something that hurts, even if the hurt wasn’t intentional? Is it fair to turn that person into a villain simply because they didn’t stay?

No, it’s not fair. But it’s also not uncommon.

This pattern of pushing others away while craving closeness is deeply tied to depression. Some individuals, especially those with early experiences of inconsistent affection or emotional neglect, develop patterns of withdrawal. They desire closeness but fear it just as intensely, equating intimacy with vulnerability, and vulnerability with pain. As a result, they learn to self-sabotage connections. Testing others, pushing them away, and controlling the terms of closeness to avoid feeling out of control.

Without appropriate intervention, these maladaptive relational patterns may solidify over time, contributing to persistent depressive symptoms and significantly disrupting a person’s ability to form and maintain healthy social connections.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Another college rejection letter.

He didn’t need to open it to know. The envelope was light, thin paper that carried the weight of yet another silent verdict. This time, it was his mother who found it first. She held it like something distasteful, already disappointed before she even handed it to him.

He opened it anyway. Read it. Folded it back up like it didn’t matter.

“Again?” she said. Her voice wasn’t loud, but there was something sharp underneath it. “What are you even doing all day? You don’t help in the house, and now you don’t even study? You can’t do either?”

He kept his eyes on the floor.

“Sweep the balcony or take out the trash at minimum, since you’re not studying.”

Later, his father said over tea, “You’re not the only one struggling, you know. Everyone has pressure. The difference is they get on with it.” No yelling. Just disappointment, worn into the fabric of their words. Familiar.

He had a lot to say.

“I tried,” he wanted to tell them. “I tried so hard.”

Ten hours a day, bent over books until the words blurred. Mock tests, schedules, notebooks filled with underlined formulas and annotations. He’d cut out everything, friends, sleep, even joy, just to chase a number that never arrived. The loneliness, the uselessness, the agony of being average.

“I studied every day,” he wanted to scream. “I gave it everything. And I still couldn’t get the rank I wanted.”

But the words stayed in his throat, stuck somewhere between shame and exhaustion. Because what if saying it out loud only made it worse? What if it made him sound like an excuse?

So instead, he nodded like he agreed. Perhaps he was just dumber than others, or perhaps he should’ve worked harder. It was easier than explaining how effort didn’t always mean success.

He joined a government college somehow. It wasn’t grand. The buildings looked tired, the labs were outdated, and the professors taught as if they were doing everyone a favour. The placements were barely placements, a handful of low-paying jobs that made it clear you’d have to fend for yourself after graduation.

But the fees? Still crushing. His parents didn’t fight much. But when they did, it was always about him, about this.

When his parents sighed over the latest notice, when his father sat at the edge of the bed rubbing his temples in silence, when his mother avoided his eyes while stirring tea she didn’t drink.

He felt unworthy of costing so much.

He wasn’t worth the investment, and some part of him had always known that.

He would sit in his room, headphones on with nothing playing, letting their muffled voices bleed through the thin walls, not really to block them out, but to create the illusion that he was trying, because the truth was, he never tried to console himself, never told himself it would be all right, never reached for even the smallest thread of hope, because somewhere deep inside, he felt like he needed to feel this way, needed the weight of it pressing down on his chest, needed the sadness and failure to wrap around him like a punishment he just didn’t want to escape.

VR glitches again

He sat through every round of placements. He got none.

He wanted to go out and drink with his friends like everyone else did after interviews – loud, tipsy, relieved. But he couldn’t. He had no friends. Not anymore. Conversations had slipped away like everything else, unnoticed, unremarked. No fights, no dramatic exits. Just people drifting. He didn’t even blame them.

This was just life now. Ongoing. Indifferent.

Until one day, it was too much.

It was the last round of placements. His last shot. He sat in a corner of the seminar hall, his formals slightly crumpled, the borrowed tie a little too tight around his neck. His hand twitched on his knee. He could feel the sweat under his arms, cold and sour. He didn’t even want a good role anymore. He just needed something. A desk, a title, a reason.

It wasn’t just a job. It was proof. Proof that the past few years hadn’t been pointless. That the anxiety attacks before exams, the sleepless nights cramming concepts he barely understood, the quiet meals alone in the mess, all of it meant something. That he meant something.

But when his name didn’t come up again, something inside him didn’t break. It simply gave way, like a muscle too tired to clench.

He walked back to the hostel as if underwater. The world was still moving, noisy, full of motion and plans.

His room greeted him with the same peeling posters, the same half-used notebooks filled with once-hopeful scribbles. He sat at the edge of the bed. He didn’t cry. That would have implied something fresh, something still alive inside him.

Instead, he began to remember things. Aanya’s voice, soft, patient, once asked him if he’d eaten lunch that day. He remembered the old friends who had tried, once upon a time, to reach through his silence. He remembered laughing with his parents as a child. Before the shouting, before the shame, before their voices dropped into exhausted murmurs about loans and “what will he even do now?”

STOP! STOP YELLING! He cried to the walls.

The peeling paint, the cracked plaster, the fan that spun like it didn’t care whether he breathed or not.

He stood there, breath ragged, fists clenched, the silence after his scream louder than anything he’d ever heard. In that silence, the weight of years came crashing down – not from outside, but from within.

He resented himself.

For pushing everyone away.

For being cruel when people tried to care.

For not saying “thank you” when they showed up.

For making sarcasm his second language and silence his shield.

For turning kindness into something suspicious, and love into something disposable.

He thought of Aanya, how gently she waited. His old friends, how they tried to stay. His parents, how they once held his hands when he cried after failing a math test, long before disappointment became their only language.

He hated how he shut them out. He hated that they stopped trying. But most of all, he hated that he understood why.

He didn’t fight for anything that mattered. And now, he had no one left to fight for.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Chronic loneliness has been shown to have serious psychological and physical impacts. Studies link it to increased risks of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and even heart disease. It can affect memory, immune function, sleep, and self-worth. Over time, loneliness doesn’t just feel like a void—it becomes a distortion. It whispers that you are fundamentally different, that your presence is unnecessary, and that your absence might not even be noticed.

And yet, loneliness is one of the most common human experiences. It is not a weakness or a personal failure. It is often a symptom of larger disconnections between people, within families, across communities and cultures that prioritise performance and productivity over emotional truth. In silence, loneliness grows. In shame, it deepens.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

That night, he lay still, eyes fixed on the ceiling fan. The hum of it was strangely soothing, a low mechanical lullaby. Outside his window, the world kept moving, scooters honking, boys laughing in the corridor, someone playing music far away. Life, ongoing.

He looked at the ceiling and thought: It doesn’t matter anymore.

And for the first time, he didn’t feel scared. He felt quiet. Peaceful, almost. There was only a note. A plain goodbye.

And then he committed his cruelest act upon himself and his family. He didn’t look back on how his absence will wreck the ones who still love him, quiet and omnipresent love that he never saw in the deep bunkers of loud disappointments and worry.

He left the room in perfect order, with a heart full of hopelessness.

VR is now shutting down

Meera didn’t know how long she had been standing there.

The headset had slipped from her hands at some point, landing softly on the bed, its voice long gone silent. The air in the room was still, heavy, like the weight of everything she had just seen was pressing down on her chest.

She stumbled back, one hand on the wall, the other still clinging to the suicide note like a lifeline. Her breath hitched. A sob – raw, involuntary. Rising from somewhere deep in her chest, as if the grief had finally found its voice.

She stepped out into the hallway, dazed.

Her husband sat there, as he always did these days, hunched over the photo album on his lap. A picture of Madhav as a toddler stared up at him, toothless grin frozen in time.

When Meera entered, he didn’t look up.

She walked to him slowly, almost cautiously, like she was approaching something fragile.

And then, without a word, she sank to the floor beside him.

He didn’t ask what happened. She didn’t explain.

She simply leaned against him, her head resting on his chest, her shoulders trembling with the weight she had carried alone for too long. His arm came around her slowly, almost uncertainly, until his hand rested at the back of her head.

They stayed like that. Two people broken open by the same loss, finally falling into each other, not in comfort, but in recognition.

There, in the quiet of a house that had forgotten how to laugh, they cried together, long and soundless.

Could this house, hollowed by loss, ever be a home once more?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Grieving a loss to suicide is unlike any other kind of bereavement. This story is not an attempt to explain suicide or reduce it to a neat narrative. Instead, it seeks to reflect the quiet devastation it leaves behind, and to acknowledge the painful truth: sometimes love was present, and still, it was not enough to save them.

Suicide rarely stems from a single event or failure. It is usually the result of a complex interaction between mental illness, internalised pain, social pressure, and a distorted sense of self-worth. Talking about suicide openly and without shame is painful, but it is also necessary, not to assign blame or find perfect answers, but to humanise the experience and remind ourselves that the people we lose to suicide were more than their last moment. They were full lives. Full of effort. Full of unseen battles.

If you take anything from this story, let it be this: grief after suicide is not something to “move on” from, but something one learns to carry. And carrying it does not mean forgetting. It means honouring the memory of the person we’ve lost while also learning to keep living.

If you are someone in grief, I hope you find permission to feel it in your own way, without rushing, without shame. If you are someone supporting a loved one through loss, may you remember that presence matters more than perfect words. And if you are someone struggling with your own pain, please know that your story is not over. You are not alone, and help exists, even if it feels distant.

I thank you for reading.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………