By Aashna Jha, Batch of 2022

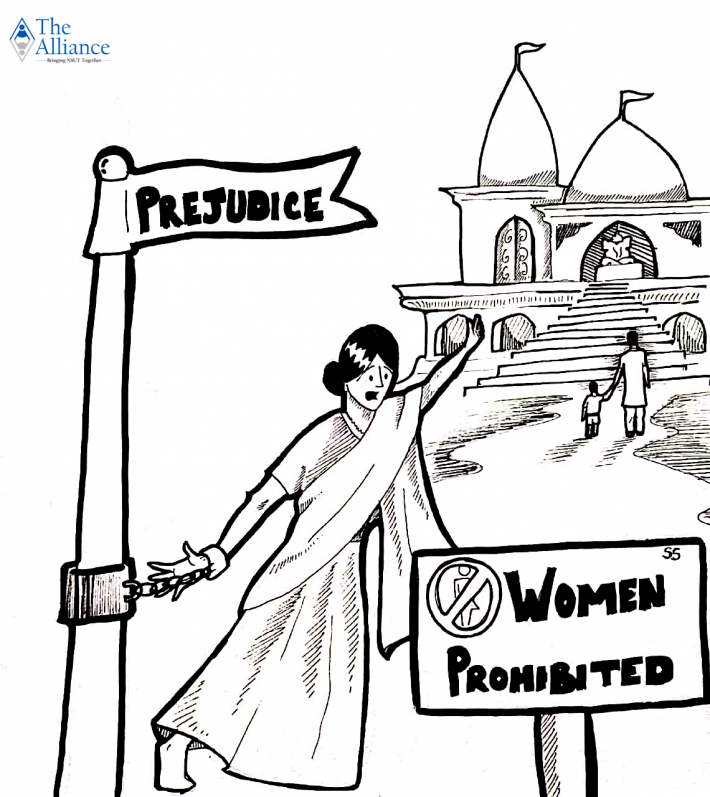

On 28th September, in a landmark judgement the Supreme Court of India lifted the ban on women from entering the Sabarimala temple, the abode of the celibate Lord Ayyappa. While a consensus was reached after much discussion and debate, dissent continues to exist. Sabarimala case emerges as a peculiar one because it isn’t a simple battle between the liberals and the conservatives but a debate lying in a grey area. Both sides hold moral justifications that are constitutionally valid but the topic remains sensitive due to the many religious sentiments involved.

Our constitution grants us the freedom of religion. While a fraction of it allows every individual to practice the religion of his/her choice, another part gives protection and independence to various religious denominations. Dissenters argue that Lord Ayyappa’s devotees deserve the same independence from court. Men wishing to enter the temple are also required to fast for 41 days, giving up meat, alcohol and practicing abstinence. Considering the notions of purity surrounding the worship of this deity, people argue that religious matters and customs are not for the court to decide.

These arguments fall short due to several reasons. As mentioned by various judges on the panel, the devotees of lord Ayyappa do not constitute a separate denomination, but rather are a part of the Hindu religion itself. Hindu scriptures and practices do allow women to enter temples and other religious grounds and therefore Sabarimala temple cannot be an exception to this rule. The stigma around menstruation and the restrictions imposed on menstruating women also plays a major role in banning women from entering the temple. In this age of science and information, such practices based on superstition and myths hold no ground. Barring women entry on the grounds of a natural and completely normal biological process comes under the practice of untouchability. The assumption that women cannot practice the 41 days abstinence period is also based around preconceived notions and devotion cannot be subject to gender stereotypes.

One might argue that the court does not have the right to make changes to the traditions attached to the worship of lord Ayyappa but a quick look into the history of Sabarimala completely negates the thought. Old Hindu scriptures and writings don’t mention Lord Ayyappa, making it difficult to ascertain the cult as strictly Hindu. Moreover its absence in northern parts of the country further blurs its origin. Certain non Brahmin origins such as the god Ayyanar of Tamil Nadu are associated with Lord Ayyappa. Some historians argue that the strict regime followed two months before the pilgrimage resembles Buddhist practices. The presence of Vavar (a Muslim deity) inside the temple and its relations with the Arthunkal church further add to its mixed religious culture.

In 1950 the Sabarimala arson case took place, portrayed to be a deliberate attempt. This lead to several ritual changes after the Hindu Mahamandal made appeals to Hindus. One such change was the restriction on entry of women, a practice which previously wasn’t in place. In 1983 attempts to build a church, near the Sabarimala, were made. This lead to a mass Hindu mobilisation popularly known as the Nilakkal movement. Such a protest against the church united a large number of Hindu devotees leading to further Hinduisation of the temple. The fact that a temple of such diverse religious origins is now a male Hindu dominated space is the subsequent result of the Hinduisation of the Sabarimala temple over the 20th century. The clampdown on women of menstruating age entering the temple is not another age old tradition but the consequence of recent changes.

Justice Indu Prakash, the only female judge in the panel, in her dissenting opinion stated that the court “cannot impose its morality or rationality with respect to the form of worship of a deity”. Her views give greater importance to the religious freedom held by an institution rather than an individual. As valid as her opinion may sound, it does go against the basic fundamental right of women to practice religion.

The crux of the matter remains that in the 21st century no authority, no organisation and no community should hold the power to withhold the right to pray from any individual. Our constitution is structured upon the principle of equality and freedom, from discrimination in any form. Segregating and restricting a devotee on the basis of gender goes against the basic ideals of our country and in a secular country like ours, the right to pray cannot be denied.