Authored by Anusha Nagpal & Iba Shibli, Batch of 2028

Caricature by: Dishita Grover, Batch of 2028

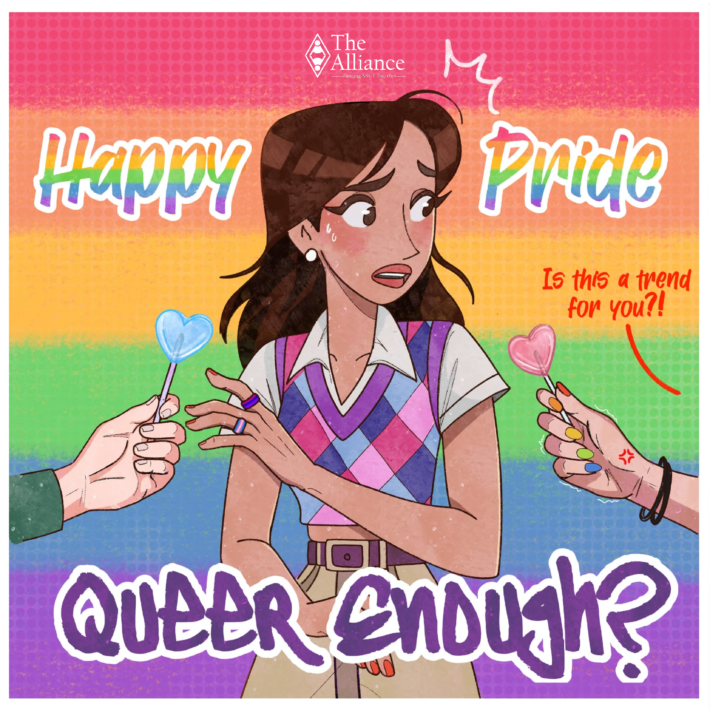

Pride has long stood as a symbol of resistance, resilience, and the freedom to love. From the Stonewall riots to the silent protests during the AIDS crisis, queer people have fought relentlessly for the right to exist, love, and live openly. Every right won today was paid for with the courage of those who risked everything simply to exist. In India too, the fight has been tough. In 1992, a group of queer activists in Delhi staged the country’s first public LGBTQ+ protest to oppose police harassment, a moment often overlooked but crucial in laying the foundation for future resistance. Since then, India’s queer movement has grown through a mix of legal battles, and public defiance—culminating in the 2018 Supreme Court judgment that decriminalized homosexuality. Despite all this, acceptance and inclusion within the LGBTQ+ community are often conditional, granted only when individuals conform to the prevailing definitions and expectations of what it means to be queer. Within the community known for its acceptance, there are many who still struggle to be recognized and accepted. These people are neglected, not only by the outside world, but also within the spaces where they are supposed to feel safe and express themselves. Deep-seated biases persist in these spaces, sometimes subtle but often harmful, undermining the very principles of solidarity and acceptance. Asexual people are told they’re broken, disabled queer people are desexualized or fetishized, and people from oppressed castes are often tokenized or erased altogether. These forms of exclusion point to a troubling truth: many of the most vulnerable people within the LGBTQ+ community have no one to turn to, not even the community itself. Among the many issues faced, there are two persistent problems: transphobia and biphobia within the community. The prejudice towards transgender and bisexual people is reflected in their exclusion from certain queer spaces, the erasure of their identities in conversations about LGBTQ+ rights, and the harmful stereotypes that persist even within the community. These patterns point to deeper issues about what it means to be part of the queer community and raise the question of who ultimately gets to decide when one is “queer enough.” Transphobia manifests itself in multiple ways, including refusal to regard transgender identities and experiences as valid. Biphobia appears through stereotypes that bisexual people are “attention seekers.” Together, these forms of prejudice highlight ongoing struggles around identity, visibility, and acceptance.

Transphobia within the queer community often shows up as denial or dismissal of transgender identities, which tends to stem from deeply ingrained ideas about gender being strictly male or female. These rigid beliefs ignore the realities of people whose gender doesn’t fit neatly into those categories, which leads to transgender individuals being pushed aside or overlooked. Many trans people face doubts about whether their identity is “real” or “valid,” encountering attitudes that question their right to define themselves. This skepticism can create real barriers, making it much harder for them to find acceptance and connection within the community, which can cause feelings of isolation and exclusion. Beyond that, harmful stereotypes persist—like the misconception that being transgender is just a phase, a choice, or confusion—despite clear evidence and lived experience to the contrary. These false ideas contribute to stigma and justify unfair treatment, not only from society at large but also within the queer community itself. Transgender people frequently encounter difficulties accessing important healthcare, legal protections, and social support, and sometimes the lack of understanding or acceptance from fellow queer people makes these challenges even harder. This internal transphobia fractures the unity of the queer movement and complicates efforts to advocate for everyone’s rights. The fact that these prejudices continue to exist shows how deeply societal norms about gender are embedded, even in spaces fighting for inclusion. To move forward, it’s essential to recognize and confront transphobia honestly so the community can become truly inclusive, welcoming all gender identities without hierarchy or exclusion.

Biphobia was first defined in 1992 as the ‘prejudice experienced by bisexuals from straight and gay individuals’, but it is far from irrelevant now over three decades later. As the queer community comes together at parades and celebrations, the biphobia that has always been an undercurrent in the community, pollutes the shades of Pride. Often, this biphobia is concealed under a veil of the notion that people identifying as bisexual have it easy. These sorts of claims are supported by the logical fallacy that bisexuals can pretend to not be gay, that their queerness is just a state of experimentation, and eventually they will settle down with someone of the opposite gender. This rhetoric has led to the severe exclusion of bisexual people from the queer community, they are shamed for not being “gay enough” when in heterosexual relationships and are made to feel unwelcome and uninvited in queer spaces. Unsurprisingly queer women are more likely to be at the receiving end of the rampant biphobia from the queer community. It is not enough that they are sexualised and stereotyped as cheaters, they are also seen as unworthy by other queer women. ‘Gold Star Lesbian’ a term that has come up in the online queer community refers to a woman attracted to women who has never been romantically linked with a man, promoting the idea that a gay woman is more desirable if she has only been with women, this actively ostracizes any woman who identifies as feeling attraction to more than one gender. This also extends to transgender people, insinuating that a relationship between a cisgender woman and a transgender woman is a heterosexual relationship and not a “real” lesbian relationship, not only invalidates the identity of both the participants as women loving women (WLW), but also blatantly misgendering transgender women. This issue is not localised to the WLW community, it comes up everywhere, labels used for various sexualities have always been weaponized against transgender people to misgender them.

In 1991, the Church of England released a statement declaring bisexuality to always be wrong because it inevitably involves being unfaithful and thus subverts monogamy. Not just the Church, most religious and moral structures paint non-monogamy as impure, and since bisexuality is viewed as inherently nonmonogamous, it is demonized. The idea of being attracted to more than one gender crumbles the idea of finding one perfect partner for life, because if a person is attracted to men and women, how can they settle down for their entire life with a person of one of these genders without also desiring a person of the other gender? This is what gives birth to the stereotype of bisexuals as cheaters. Bisexuals are accused of being confused about their feelings of attraction far too commonly, but a trend that has emerged over the years is that bisexual women are more likely to be assumed to be straight and bisexual men are more likely to be assumed to be gay. Effectively this centers the conversation around men, and is a clear manifestation of patriarchal ideas that survives even in the queer community, a community that is fundamentally subversive to the patriarchy. The invalidation of bisexuals persists in the form of ‘queer-baiting’. Queer-baiting describes a marketing tactic wherein the creator will hint at LGBTQ+ representation without any real depiction. It is a marketing tactic for fiction and entertainment, it does not apply to real people. Nevertheless in recent years the queer community has often accused celebrities of ‘queer-baiting’, prying into their private lives and going as far as forcing them to come out. Bisexuals are often at the end of these accusations, a person openly identifying as bisexual, enters into a heterosexual relationship and suddenly they are seen as betraying the queer community, their bisexuality is seen as something they used to pretend to be cool or seek attention. One could dress this up as activism, but that would be a band-aid put over what is ultimately textbook homophobia. And when these sorts of accusations shift from celebrities to people who one knows, friends and acquaintances, outing people who live in queerphobic environments can have violent, devastating outcomes.

A large chunk of biphobia boils down to the invalidation of the identity of bisexual people, this issue is very real and prevalent in and outside the queer community but it is painted as if to be not that big of a deal. This is incredibly damaging to the lives of bisexual people. Multiple surveys over the years have uncovered that people identifying as bisexual are at an increased risk of ill health. A 2019 study by the Canadian Government found that bisexuals have higher rates of chronic diseases, poor mental and physical health, smoking and alcohol use as compared to gay, straight and lesbian people. In 2017, a review by The Journal of Sex Research of over a thousand studies from across a decade revealed that non-monosexual people are the most likely to experience depression, anxiety and poverty among all other sexual minority groups. The list doesn’t end here. Another review in 2018 shows that bisexuals experience a higher risk of suicide and suicide ideation, and a 2020 study found that among all sexual orientations, bisexuals are most likely to self-harm. This discrepancy among bisexuals and other identities under the queer umbrella regarding health outcomes, is glaring proof of the negative impacts of biphobia on the lives of bisexuals.

The harm of being pushed to the margins doesn’t end with just feeling excluded — it shapes how queer adults live, survive, and are treated every day. Many face real-world struggles that go far beyond identity. Finding a job where you’re safe to be yourself is still a privilege, not a guarantee. Trans and visibly queer people are often denied work or forced to hide who they are just to stay employed. Healthcare is no better — doctors can be dismissive, untrained, or outright hostile, especially when it comes to gender-affirming care. Even getting a regular check-up without being misgendered or mocked becomes a challenge. Safe housing isn’t always an option either, with many being turned away by landlords or harassed by neighbours. And when queer people are in danger — from family violence, public harassment, or even assault — the law often looks the other way. Same-sex relationships still aren’t legally recognized in India, which means queer couples are invisible when it comes to rights like inheritance, insurance, or making medical decisions for a partner. Some are pushed into heterosexual marriages, others sent to conversion therapists, and in extreme cases, people face “corrective” violence, all because they don’t fit into what society deems acceptable. For many queer adults, especially those who are Dalit, disabled, or from poor or rural backgrounds, there’s often no one to turn to — not even their community. All of this stems from the same systems that have always controlled people’s bodies and choices — patriarchy, caste, and rigid ideas about gender and family.

A community that is no stranger to being discriminated against based on stereotypes associated with how they present, to being outed and to having their identity invalidated seems to have no problem levelling these against members of their own community. The venn diagram of bigots and members of the LGBTQ+ community has a worrying overlap, and while acceptance within the queer community has increased over the years there is still a long way to go. This could be attributed to the internalised queerphobia that almost all queer people are victims to. Growing up in a space where anti-LGBTQ+ values are deeply rooted, coming to terms with one’s own identity is complicated, and it can take years for one to unlearn this hate. However this cannot excuse the actions of queer people that cause harm to the community as a whole. Despite being a community for people who do not fit into the conventional box, there has been a marked increase in policing the labels that individuals can use for themselves. The rejection of specific identities under the queer umbrella to advance one’s own rights as a queer person directly opposes the essence of Pride. The public face of Pride, the least marginalized members of the queer community, show a lack of solidarity to the queer people who are the most marginalized. This means that white, gender conforming, gay and lesbian individuals make significant headway, while gender non-conforming and queer people of colour are still seen as “unnatural”. Undoubtedly there has been major progress in the fight for acceptance, but it is still not enough and the dismissal of bigotry within the queer community hinders the progress of the queer movement. Pride is about liberation, the freedom to express one’s identity but it is also about standing with all the people who are victims of the racist and patriarchal structures that govern our society. Transgender people and queer people of colour have been continually denied a seat at the mainstream table in order to appeal to the heteronormative, cisgender people handing out basic human rights only to those that they deem “normal queer”. The fight for acceptance is not a victory until every queer person no matter their sexuality, no matter their gender, no matter their race, no matter their caste, is visible in the struggle for equality and can truly share in the full dignity, freedom, and joy that the LGBTQ+ movement has long fought for.